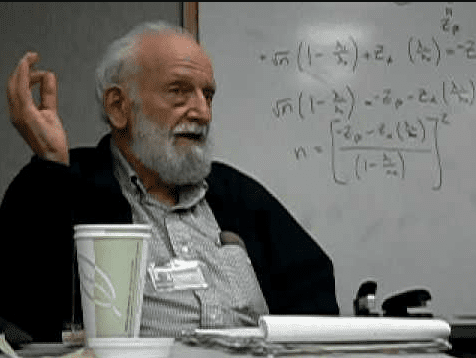

Richard Levins was born in Brooklyn in 1930. Like many Brooklynites, his family had immigrated to the United States. He had both Ukrainian and Jewish roots. From a young age, Levins displayed remarkable intelligence and an intense interest in science. At just eight years old, he read Microbe Hunters by Paul de Kruif. By the age of 12, he was already exploring Darwin’s theory of evolution, showing an early fascination with species’ origins and adaptation.

One of the biggest influences on his scientific and ideological development was the work of John Burdon Sanderson Haldane, a renowned biologist and Marxist thinker. To the young Levins, Haldane was the Einstein of biology, shaping both his academic and political outlook. Levins was a staunch Marxist, a perspective that would define much of his career.

Despite his political leanings, Levins initially pursued agricultural science and mathematics at Cornell University. However, he never completed his degree, as he was expelled under unclear circumstances. Nevertheless, in 1965, he earned his PhD from Columbia University. During his university years, he met writer Rosario Morales, and after his expulsion, they moved to her homeland, Puerto Rico, where he took up farming. More on brooklyn-name.com.

An Active Social Stance

While living in Puerto Rico, Levins was not only growing crops like corn and potatoes but also actively teaching. Between 1961 and 1967, he was a faculty member at a local university. He also became involved in the Puerto Rican independence movement, a political stance that ultimately cost him his teaching position.

In 1964, he traveled to Cuba, where he quickly formed scientific and political connections that would last a lifetime. By 1967, he moved to Chicago with his family and began teaching at the University of Chicago. Later, they relocated to Harvard University, where he was elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States. Despite his strong personality and often controversial views, he was widely respected in academic circles.

Levins was a passionate pacifist, and he resigned from the National Academy of Sciences in protest when he learned they were advising the military during wartime. While he opposed war in America, he remained drawn to revolutionary movements worldwide, which attracted the attention of the FBI.

However, he remained involved in several key initiatives. Until his death, Levins chaired the Human Ecology Program and was part of the Department of Global Health and Population at Harvard.

In the 1990s, alongside other scientists, Levins helped establish the Harvard Working Group on New and Emerging Diseases. Their primary conclusion was that new infectious diseases were not solely the result of environmental changes but were equally influenced by human activity. He argued that both natural and human factors contributed to the rise of new diseases, making it difficult to assign blame to just one cause.

Scientific Influence

For the last 20 years of his life, Levins focused on applying ecological principles to agriculture, particularly in developing countries. He studied how environmental factors impacted agricultural productivity and development.

Levins also served as the director of OXFAM-America and conducted extensive research on the industrial and economic development of Latin American and Caribbean countries. He sought to address economic efficiency, ecological and social sustainability, and the rights of marginalized communities.

He remained active in academia until his passing. After his wife’s death in 2011, he moved in with his daughter in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he died in 2016.

Challenging Genetic Assumptions

One of Levins’ key contributions was revolutionizing the fundamental understanding of genetics. Previously, population genetics assumed that environmental conditions were stable. However, mathematical ecology suggested otherwise. According to Levins, the genetic structure of species remained constant, but the environment was ever-changing.

He developed a model demonstrating how species evolved in response to a shifting environment. His findings led to an unexpected conclusion: previously, scientists believed that species that had been naturally selected were the most adaptable and resilient. However, Levins’ research suggested the opposite. He found that these selected species could ultimately lead themselves to extinction. Rapid environmental changes could force species into such extreme evolutionary adaptations that they became incapable of reproducing in the future. His groundbreaking insights, often incorporating mathematical models borrowed from economics, significantly reshaped evolutionary theory.

Introducing the Concept of Metapopulation

In 1969, Levins coined the term metapopulation to describe a model of “populations of populations.” His idea proposed that each population occupied a distinct area, creating a habitable zone. Within each of these zones, a subpopulation emerged. When a local population went extinct, neighboring subpopulations from a larger metapopulation would migrate in and repopulate the area.

The concept of metapopulation became a cornerstone of geographical ecology. Scientists began applying it to biodiversity research, population management, and pest control. The latter had a particularly strong impact on agriculture, transforming strategies for sustainable farming.