The massive gray buildings of the cement factory stretching along the Sunset Park waterfront between 30th and 37th Streets are the remnants of Brooklyn’s largest industrial park—Bush Terminal. This complex was the brainchild of Irving T. Bush, the son of an oilman turned yachtsman. Today, these buildings are known as Industry City, a growing complex that provides jobs for Brooklyn’s creative economy while anticipating the arrival of future dining establishments, entertainment venues, and shops. Read more at brooklyn-name.com.

Father and Son

Many believe the story of these buildings begins with Irving T. Bush’s personal journey. In a way, that is true—he was born into a wealthy family that owned an oil refinery on the Sunset Park waterfront in Brooklyn. At 18, he joined his father in ocean yacht races; at 19, he sailed around the world on a yacht; and by 21, he inherited half of his father’s fortune. However, his father, Rufus Bush, also played a significant role in this story, perhaps unknowingly, so leaving him out would be unfair.

Rufus Bush was a remarkable salesman and a founding partner of the small Bush & Denslow Company oil refinery in the 1870s, then located near 25th Street in what was called South Brooklyn. His company found itself in an uneven competition with John D. Rockefeller, Charles Pratt, and their Standard Oil—today, this rivalry could be compared to a small local gas station competing with Exxon. But Rufus got lucky.

When the government cracked down on Big Oil with antitrust laws, Rufus was called as a witness. Newspapers began quoting him, turning him into a media personality. His public appearances caused such a stir that Standard Oil eventually decided to buy out his company just to silence him—and he didn’t put up much of a fight. After closing the deal, Standard Oil demolished his refinery, while Rufus bought a yacht and spent years at sea, taking his wife and children on a worldwide voyage.

In 1890, Rufus Bush passed away, leaving behind an estate worth $2 million—a considerable sum at the time. The money was immediately funneled into the Bush family corporation. This is where Irving stepped in, taking charge of the company, which owned the rights to sell Edison’s early motion picture system, the kinetoscope, among other ventures.

However, after opening the first European kinetoscope parlor in London in 1894, he left the film business and turned his attention to transforming the former oil refinery site into the world’s first large-scale integrated transportation, warehousing, and manufacturing facility. For many years, it remained just that. At its peak, over 25,000 people worked at what later became known as Bush Terminal. But before that, Irving’s first move was to buy back his father’s former oil refinery in Sunset Park.

A Grand Idea

The key to attracting tenants was the construction of large new buildings with open floor plans—unlike the overcrowded, much smaller lofts in Manhattan and other parts of Brooklyn. Bush Terminal offered direct access to railroads serving Long Island and reaching the mainland via Queens. Its docks allowed ships to deliver raw materials or finished products, which could then be transported efficiently. Just as important was the proximity to related industries.

But that wasn’t all—Bush had another ace up his sleeve. He built a 30-story neo-Gothic tower near Times Square in Manhattan. The Bush Tower provided free office and exhibition space for businesses at his terminal, allowing them to meet and trade with out-of-town buyers who came to the city to purchase goods for stores and factories across the country.

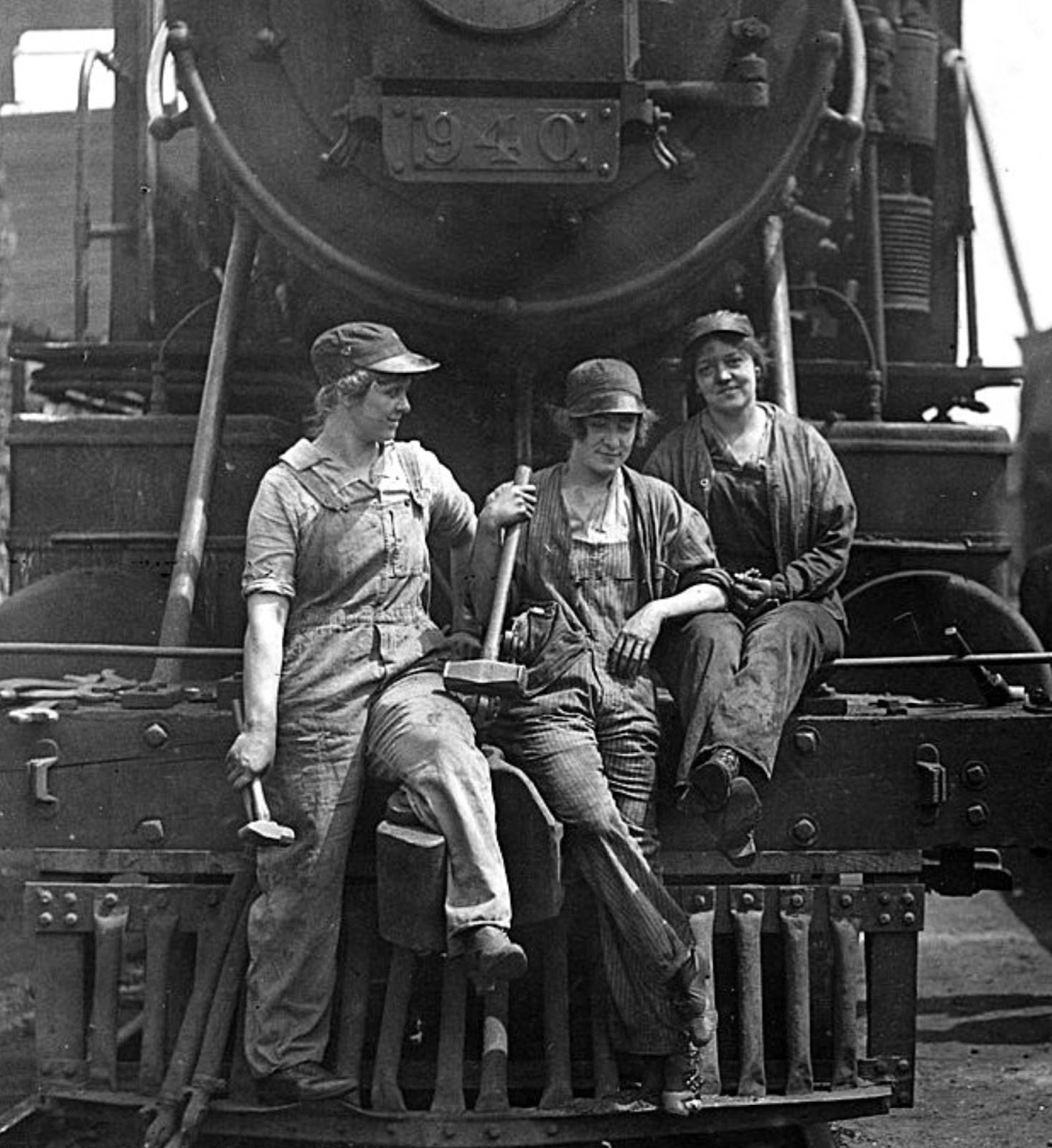

During World War I, most of Bush Terminal was used as a naval base, with its piers and railways dedicated to manufacturing, loading, and shipping wartime supplies to the Allies. Like many other workplaces, the war opened up new opportunities for women, who took on jobs previously unavailable to them, including positions on the terminal’s railway.

Bush Terminal survived the Great Depression, although it did go bankrupt in the process, and continued operating during and after World War II.

World War II

During World War II, Bush Terminal was the largest multi-tenant industrial complex in the United States, employing over 20,000 people. It functioned as a self-sufficient city with its own power plants, private railway, streets, police, and fire services.

However, the postwar years were not kind to the company. Manufacturing began shifting away from urban centers, cargo moved to larger and, eventually, containerized ships, and the rise of long-haul trucking reduced the importance of rail connections. By 1948, after seeing his vast enterprise endure two world wars, Irving T. Bush passed away at the age of 79. Whether he would have been pleased with the future of his terminal is uncertain.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the terminal was renamed Industrial City. Plans for revitalization were developed, and the complex was marketed to artists, craftspeople, and small-scale manufacturers.

A new art gallery—The Marion Spore Gallery—was established on 33rd Street, named after Irving T. Bush’s third wife, a controversial and well-known artist. Unfortunately, the gallery has since closed.

Meanwhile, in the 1970s and 80s, large sections of the complex sat vacant, and some outer buildings were demolished—one part to the south made way for a shopping center, another to the north for the construction of a federal prison. The piers were filled in and replaced with a park. The northern rail station was shut down, and its tracks along Second Avenue were paved over.

A New Century Brings New Life

In the 21st century, various projects injected new life into the area, adding artist studios, tech company spaces, and more. However, by 2012, a third of the space remained empty, with only 2,500 people working there. That same year, new developers acquired part of Bush Terminal under the Industry City banner and began renovations to rejuvenate the area. Discussions about expansion followed, though they have yet to materialize on a large scale.

The arrival of Costco and other retailers in the area attracted people to Bush Terminal for the first time in years, while major companies like Time Inc. and Amazon leased office and warehouse space.

A Billion-Dollar Redevelopment

Among the more unusual tenants of the complex is a rooftop facility operated by the Hospital for Special Surgery, as well as the training center for the NBA’s Brooklyn Nets. The interior courtyards of the buildings have been transformed into open spaces for live music, food vendors, art installations, and seasonal decorations like pumpkins and skeletons.

New plans for this historic site continue to take shape. Local food vendors and artists remain active, while Brooklyn Flea and Smorgasburg boost foot traffic on weekends during the winter months.

Additionally, since 2015, the owners have been developing a $1 billion redevelopment plan. Over the next decade, this massive investment aims to repurpose and restore the complex, ensuring its place in Brooklyn’s industrial and creative landscape for years to come.