Historians traditionally study human history through preserved texts, while architecture is analyzed through images. However, the living world offers its own unique way of understanding the past. A particularly striking example is the tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima). Though now widely considered a weed, this tree was once an exotic and highly valued species. Most people associate it with the famous novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith. Yet, beyond literature, this is a tree that anyone in Brooklyn has likely seen. It truly does grow in Brooklyn and beyond, thriving across much of the United States. More on brooklyn-name.com.

Betty Smith’s Novel

You may have read Betty Smith’s novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. The tree of heaven gained widespread popularity in 1943 when it was featured as a symbol of resilience in Smith’s novel. This book tells the story of a brave and determined girl from Brooklyn’s tenement houses, with the tree representing her unbreakable spirit. It thrived in the city, where other plants wilted and died. No matter where its seeds landed, another tree would sprout, striving to reach the sky.

It grew on boarded-up lots and in abandoned heaps of garbage—it was the only tree that could push through the concrete. Over time, much has changed. Today, if you ask a city resident about the tree of heaven, they will likely tell you that its incredible resilience is actually a major nuisance. Nowadays, the tree is considered an invasive species, a problem that needs to be addressed.

Brooklyn’s municipal authorities did not always view street trees favorably, particularly in the city’s early history. In those days, they were often classified as obstacles to traffic and urban development. However, attitudes began shifting in the early 19th century as the city’s population exploded and new streets were constructed.

Even back then, tree advocates argued that greenery could beautify sidewalks, provide shade, and improve air quality in crowded, disease-prone cities. It was also believed that trees increased property values. Without municipal support, local newspapers encouraged homeowners to plant trees, reminding them every spring and fall—prime planting seasons—of the many benefits trees provided.

But could any tree survive the bustling city streets? This was a serious question for homeowners. It was not just about finding trees that grew upright enough to avoid obstructing buildings or whose roots wouldn’t damage newly installed water pipes, gutters, or cobblestones. The challenge was to find a species that could thrive despite urban hardships.

Growth time was another consideration. People wanted shade and protection from trees as quickly as possible. Early 19th-century nursery catalogs emphasized the desire for immediate shade and relief from the heat. As it turned out, such a tree existed.

A Battle Against Caterpillar Invasions

The tree of heaven not only grew rapidly but also proved highly resistant to caterpillars and other pests. This was a key advantage for American cities, particularly Brooklyn, in the mid-19th century. Between the 1850s and 1870s, many East Coast cities, including New York and Brooklyn, suffered devastating caterpillar infestations. These insects, known as inchworms, stripped the leaves from city trees, leaving bare branches. They then hung from the trees and fell onto pedestrians’ hair, beards, and clothing, or onto sidewalks, where they were crushed underfoot, creating revolting piles of insect remains.

Beyond the inconvenience of caterpillars clinging to people’s beards, there was the broader problem of urban defoliation. Before air conditioning and electric fans, shade trees were essential for keeping sidewalks and homes cool during sweltering summers. But if caterpillars devoured the leaves by early July, trees became useless for shade.

Prince Nursery

One of the earliest commercial nurseries in the United States, Prince Nursery, played a key role in the spread of tree seedlings across the country and internationally. Naturally, it also contributed to the introduction of exotic Chinese tree-of-heaven saplings.

The tree of heaven first appeared in Prince Nursery’s annual catalog in 1823. Most trees sold for 37.5 to 50 cents at the time, but the tree of heaven was among the few priced at the highest tier—one dollar per tree. There was a minor mix-up at first: William Prince mistakenly identified it as the Tanner Sumac. However, once the error was corrected and its exotic origins from China were highlighted, the tree quickly gained immense popularity. For many years, demand for it tripled supply, keeping its price high. In Brooklyn, the tree of heaven was in particularly high demand.

A close look at the tree of heaven reveals that it doesn’t quite blend with the Northeastern landscape. This makes sense—it isn’t a native American species. Originating from China and Taiwan, the tree made its way to Europe in the early 18th century when English landscape designers were enamored with Far Eastern gardens. It arrived in America a decade later, in 1784, when Philadelphia horticulturist William Hamilton planted the first specimen at his estate, The Woodlands.

Over the following decades, the frost-resistant tree gained widespread popularity as an exotic ornamental plant, particularly for urban landscaping. Its ability to withstand pollution further solidified its appeal. However, the tree also had its downsides. It releases toxins to suppress competing plants, and its male flowers emit a foul odor during bloom.

Challenging the Urban Environment

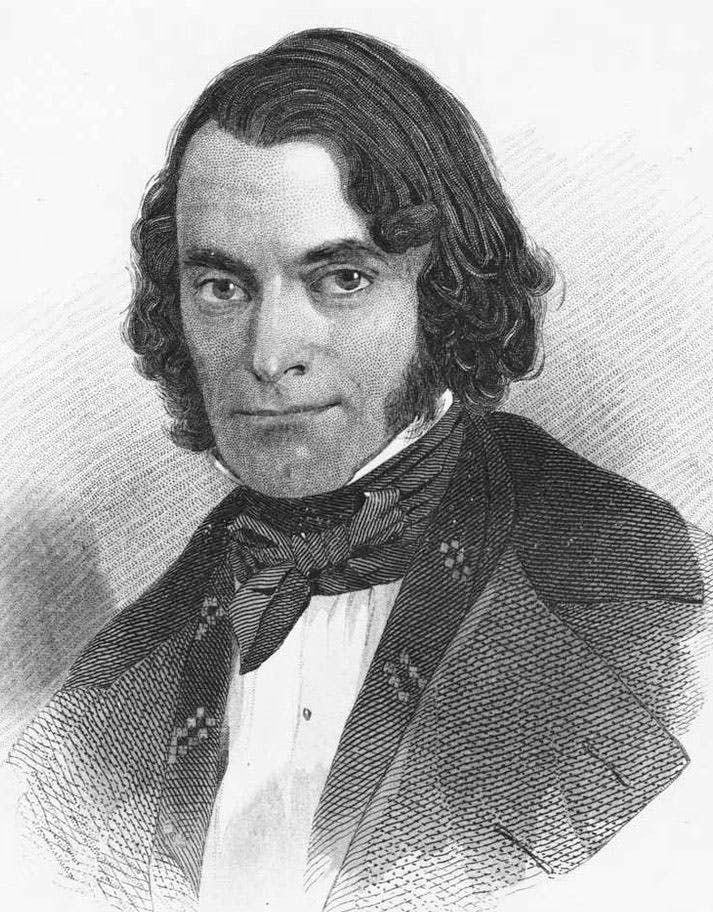

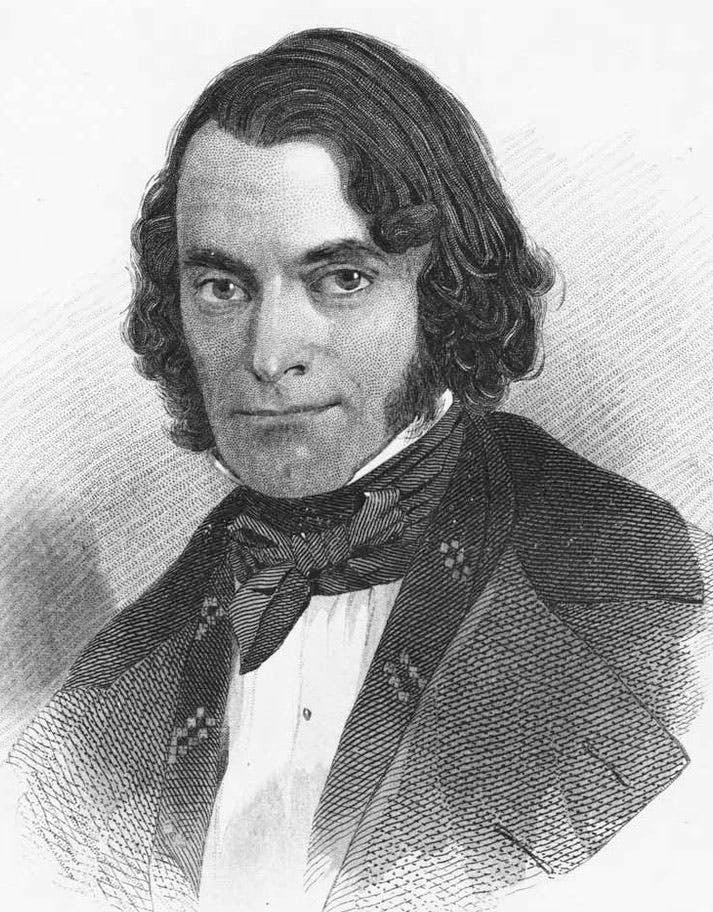

Andrew Jackson Downing, widely considered the father of American landscape architecture, predicted the decline of the tree’s popularity as early as 1852—ironically, at the peak of its acclaim. In his journal The Horticulturalist, he warned about its rapid spread and its less appealing traits. Instead, he advocated for more beneficial native tree species. But at the time, few listened.

Urban environments often feel like controlled spaces, but the tree of heaven defied that perception. It served a purpose in the early 19th century, offering almost instant shade and requiring little maintenance. It thrived on Brooklyn’s rapidly developing, newly paved streets, resisting infestations that plagued other trees. And, as Betty Smith’s novel famously reminds us—A Tree Grows in Brooklyn.