Thanks to meticulous planning and execution nearly 150 years ago, Prospect Park appears today as if it has always been there. That was precisely the idea behind its creation.

For those unfamiliar with its history, it might seem that all landscape designers had to do was enclose the park with a fence, carve out a few roads and pathways, build some bridges and grand entrances, mow the lawns, and most importantly, create a body of water.

However, the construction of Prospect Park was far more complex. One of its crowning achievements was the development of a man-made lake, which remains a standout feature of the park today.

More details on the park’s construction and the creation of its water system can be found on brooklyn-name.com.

The Early Development of the Project

In reality, Prospect Park was constructed with the same level of careful planning and design as the film sets of The Lord of the Rings in New Zealand.

Every aspect of both Prospect Park and the fictional Shire was carefully thought out.

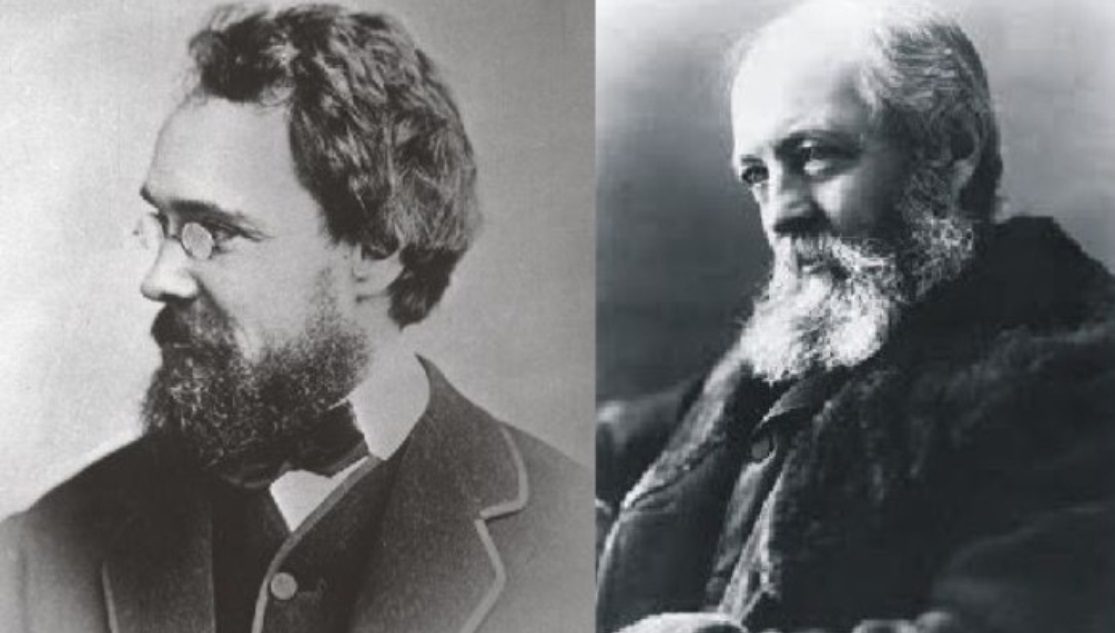

After Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted completed the construction of Central Park in Manhattan in 1857, Brooklyn sought to establish a large park of its own.

At the time, Brooklyn and Manhattan were fierce rivals, yet mutually dependent on each other.

Brooklyn city leaders quickly formed a parks committee, appointing James S.T. Stranahan—one of Brooklyn’s most influential residents—as its president.

The committee assigned the task of designing Prospect Park to Egbert L. Viele, a landscape engineer who had initially served as chief engineer for Central Park before being replaced by Olmsted and Vaux.

The general area for the park had already been selected. It included Prospect Hill, which at the time housed Brooklyn’s municipal reservoir, and Battle Pass, a historic site from the 1776 Battle of Brooklyn, one of the first and bloodiest battles of the American Revolutionary War.

Between these two landmarks lay hundreds of acres of land, much of which consisted of swamps with foul odors, believed to harbor disease and death.

Additionally, the area had rocky terrain, abandoned farmland, and scattered estates.

Viele’s park plan incorporated Prospect Hill, the reservoir, and Battle Pass, extending further to connect these features.

At its center, the park would be bisected by Flatbush Avenue, a road that had served as a major thoroughfare since the Revolutionary War.

Revising the Project and Replacing the Designer

Viele’s design embraced the area’s natural features, incorporating a parade ground, gardens, a lake, and rolling hills.

He believed the park did not require elaborate landscaping, as nature itself would provide a setting for recreation and relaxation.

By this time, Brooklyn had already begun acquiring land for the park—from Prospect Heights to the middle of Park Slope. However, before construction could begin, the Civil War broke out, delaying the project indefinitely.

In 1865, Stranahan invited Calvert Vaux to tour the proposed park site, seeking the opinion of a landscape architect.

Vaux was not impressed.

He disliked the reservoir, and he hated Flatbush Avenue, which divided the park in half with heavy traffic.

Vaux presented a report to Stranahan, proposing significant changes:

- Eliminate the eastern portion of the park that included the reservoir.

- Sell off the land already acquired in the east.

- Expand the park westward and southward, purchasing additional land.

Vaux also wrote to Olmsted in California, informing him about the project.

By the following year, the two men developed a completely new plan, which they presented to Stranahan’s committee in 1866.

Their vision for the park was based on three main elements:

- Meadows

- Forests

- Lakes

The committee was impressed and fully supported their plan.

Vaux wrote to Olmsted, urging him to return to Brooklyn. Without hesitation, Olmsted came back, and the two architects officially replaced Egbert Viele.

Starting Over

Stranahan’s committee had to reverse some of the earlier work and approve new financial investments.

By this time, Brooklyn had already purchased large portions of land, but now they had to sell some parcels while also acquiring additional land in the west.

A significant portion of the newly acquired land belonged to Edwin Litchfield, a railroad magnate and real estate mogul.

His villa was set to be incorporated into the redesigned park, and seeing a business opportunity, he did not hesitate to support the new construction efforts.

Brooklyn needed state legislature approval to secure funding for the additional land purchases, which took several years.

Meanwhile, Olmsted and Vaux focused their efforts on landscaping the western section of the park and developing Grand Army Plaza, a key entrance to Prospect Park.

Designing the Park’s Water System

Before landscaping could begin, the architects needed to control the water flow and drain the swamps.

This required the construction of a massive underground drainage system.

- Old farm structures and houses were removed.

- Existing roads were filled in.

- New roads and pedestrian pathways were designed, following both the natural terrain and the architects’ vision for an idealized natural park.

One of the most challenging aspects of the park’s design was excavating the lake and interconnected waterways—a process that took four years.

The water system had to be connected to wells, reservoirs, and pipelines to ensure that the lakes and streams remained filled with fresh water.

The water system originated from Swan Lake at the end of Long Meadow, formerly known as The Pools.

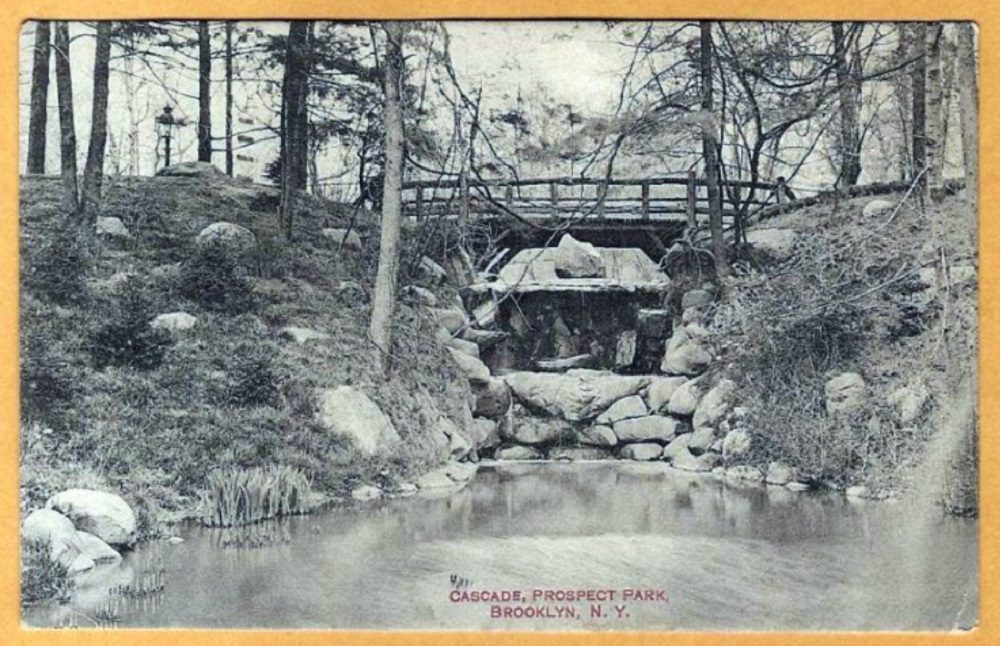

- A stream called Ambergill flowed from Swan Lake, winding through a rocky gorge before passing through Midwood and Nethermead.

- From there, the stream connected to Binnen Waters and Lily Pond, before cascading over a waterfall into Lullwater.

- The final destination was a 57-acre lake, which became one of the park’s most stunning features.

Excavation was done partly with machinery, but much of it was manual labor, requiring shovels and back-breaking work.

The eastern section of the park opened to the public in 1867 and was well received.

Construction on the western section continued until 1873, when a financial crisis halted the project.

Work remained stalled for over a decade, and it was not until 1885 that the second phase of the park was completed.

Later, McKim, Mead & White added grand entrance gates and neoclassical buildings, which were never part of the original Olmsted & Vaux design.

Prospect Park’s success made it a model for other urban parks.

Its carefully designed landscapes, lakes, and green spaces demonstrated how a man-made environment could mimic natural beauty.

Today, the park remains one of Brooklyn’s most cherished landmarks, standing as a testament to the vision and ingenuity of its designers.